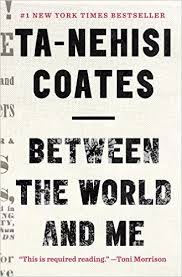

Ta-Nehisi Coates

Ta-Nehisi Coates

Spiegel & Grau

|

That was the week you learned that the killers of Michael Brown would go free. The men who had left his body in the street like some awesome declaration of their inviolable power would never be punished. It was not my expectation that anyone would ever be punished. But you were young and still believed. You stayed up until 11 p.m. that night, waiting for the announcement of an indictment, and when instead it was announced that there was none you said, “I’ve got to go,” and you went into your room, and I heard you crying. from Between the World and Me |

A father's impassioned letter to his child

“Black people love their children with a kind of obsession,” writes Ta-Nehisi Coates to his 15-year old son. “You are all we have, and you come to us endangered.”

Nominated for this year’s National Book Award in nonfiction, Between the World and Me, is a kind of updated version on “The Fire Next Time,” James Baldwin’s 1963 classic treatise on race in America that he wrote to his 15-year old nephew.

Coates, an award-winning journalist for The Atlantic and 2015 recipient of a McArthur Genius grant, has written an impassioned letter to his son that is part memoir and part social critique, trying to teach his son how “to live free in this black body.”

He realizes that much has changed for African Americans since 1963; and much hasn’t. (“Fully 60 percent of all young black males who drop out of high school will go to jail. This should disgrace the country. But it does not.”)

He tells his son of his own childhood and youth growing up on the rough streets of Baltimore, where his life was dominated by fear—fear of the gangs, fear of the police, fear of fear itself.

He came of age with the modern civil rights movement, but he primarily remembers being afraid as a boy—“Our teachers urged us toward the example of Freedom Marchers, Freedom Riders, and Freedom Summers, and it seemed that the month could not pass without a series of films dedicated to the glories of being beaten on camera.”

But he also realizes that his son is growing up in a world different from his. (“I don’t know what it means to grow up with a black president…”) With tremendous self-awareness and insight he recognizes that “I am wounded,” still bearing “the deeper weight of my generational chains,” and, like a good father, he does not want his woundedness to poison his child.

In the end, Coates wants what any father wants for his child: to have the opportunity to discover his or her human potential, and challenges the youth: “this is your country…this is your world…this is your body, and you must find some way to live within the all of it.”

Between the World and Me is an important book at an important time in this country’s ongoing effort to re-examine and redefine itself by its own most fundamental and noble principles.

This review first appeared in The Columbia River Reader (October 15-November 24, 2015.) Reprinted with permission.